Aquatic Invasive Species

Species that are non-native to Lake Champlain and likely to cause ecological or environmental harm are considered "invasive." The Lake Champlain Committee (LCC) works to prevent the establishment and spread of aquatic and semi-aquatic invasive species in Lake Champlain and its basin. In the absence of ecological controls such as disease and predators, non-native species can out-compete natives, which depletes the lake's native biodiversity.

In the summer of 2023, LCC piloted the Champlain Aquatic invasive Monitoring Program (CHAMP), which recruits, trains, and supports volunteers to survey for aquatic invasive species (AIS) at sites throughout Lake Champlain. Volunteers paddle or walk along a shoreline site, rake in samples of aquatic life, and report their findings of key target invasive species to LCC three times during the summer and fall. With the data gathered by dedicated CHAMP volunteers, management professionals can identify populations for rapid response and build a database of information on where they aren’t established. Surveys also aid in early detection and rapid response to new invaders -- we train volunteers in identification of “watch list” invasive species that have been reported in the Hudson River and other nearby waterbodies, but not yet Lake Champlain. Click here to learn more and sign up to volunteer with CHAMP.

Zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha) are small, freshwater, bivalve shellfish that were likely brought to the U.S. as stowaways in the ballast water of ships. They are native to the Caspian and Black Seas south of Russia and Ukraine, and have since become widespread in both Europe and the U.S. They entered Lake Champlain around 1993 and have proliferated. The mussels are armed with root-like proteins called byssal threads that allow them to attach to nearly any surface--including rocks, docks, and native species. This combined with their adaptability and abundant reproduction, zebra mussels can smother native mussel species, coat water intake pipes, and slice the feet of unsuspecting swimmers.

Alewives were first found in the lake in 2003 and have since become a dominant forage fish. Recent winter kills of alewives have led to tons of rotting fish washing ashore after the ice has melted, but they do not seem to have impacted the lakewide population of that fish.

Fishhook waterflea were discovered in Lake Champlain in the fall of 2018. They are native to Eurasia, and have been present in the Great Lakes since the 1980s. This invasive is similar to the spiny waterflea in appearance, and also preys on native zooplankton while it is itself a poorer food source for fish. Fishhook waterflea have a long, distinctive spine with a loop at one end, much like a fish hook, that often tangles with other fleas as well as anglers' fishing line.

Spiny waterflea were first found in Lake Champlain in the summer of 2014. The species, originally from Northeast Europe, first appeared in North America in Lake Huron in 1984. In addition to competing with native zooplankton, spiny waterflea is much more difficult for small fish to ingest, thus a poorer food source. The long spines of these species can hook them onto anglers’ lines in the hundreds, making fishing difficult.

Eurasian watermilfoil has spread throughout the lake, creating a challenge and nuisance for swimmers and boaters. The closely related variable-leaved milfoil was discovered in Missisquoi Bay and in the South Lake since 2009.

In addition to invasive species, native species can sometimes become out of balance with the ecosystem. For example, sea lamprey are a native species whose populations are currently high enough to threaten the long-term wellbeing of other native species. The Lake Champlain Committee has worked to identify and develop means of controlling sea lamprey that minimize the use of pesticides.

How did they get here?

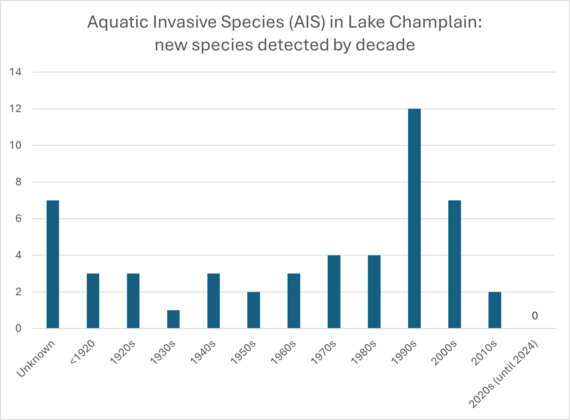

Of the exotic species whose origin of introduction to Lake Champlain is known, more than 60 percent entered via canals, particularly the Champlain Canal at the southern end of the lake. Many more species stand poised to join them. The Hudson River has over twice as many exotic species as Lake Champlain; the Great Lakes host nearly four times more.

Species on the horizon

A horde of invasive species moves closer to Lake Champlain, ready to invade its waters. The following species are currently on the hot list, and the Lake Champlain Committee is working to reduce the chance that they will be successful.

Round goby: a fish species native to the Caspian and Black Sea regions. They were introduced to the Great Lakes probably from a ship's discharged ballast water, and first found in North America in 1990 in the St. Clair River. Gobies are bottom-dwelling fish that perch on rocks and substrate. They grow up to 10 inches long and have large heads, soft bodies and dorsal fins that lack spines. Often confused with sculpins, the round goby is distinguished by its fused pelvic (bottom) fin which forms a suction disk that allows them to anchor to the bottom. No fish native to North America has this feature.

Round gobies are predators of many native fish such as darters, sculpins, and logperch. Populations of some of these species have seen substantial declines in the St. Clair River. They also eat eggs and fry of lake trout and eggs of lake sturgeon. They have been implicated in major die-offs of birds in the Great Lakes. They can harbor the bacterium that causes avian botulism; this is transmitted to the birds that eat round gobies.

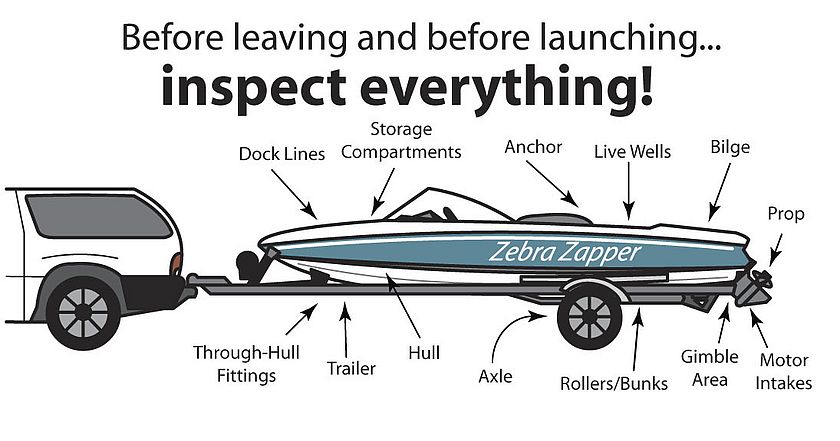

Hydrilla: a highly aggressive plant. Hydrilla has clogged drainage canals in the southeast and populations have been reported as close as Massachusetts, Maine, and Suffolk and Orange Counties in New York. A strain of hydrilla was found in the north in the Potomac Basin in the 1980s. Fragments falling from boats, trailers, and live wells can start new populations, which often begin near boat launches. Compared to other aquatic plants, hydrilla grows well in deeper, darker waters and new infestations may establish a foothold there before spreading into shallower waters and out-competing other resident plants.

VHS: viral hemorrhagic septicemia – an often lethal disease of fish that affects numerous species. The presence of VHS in the Great Lakes drainage has led to imposition of significant restrictions on transport of fish between waterbodies. VHS is such a significant disease that new outbreaks have to be reported to the World Health Organization for Animal Health. The disease transmits easily between fish (both individuals and species) and mortality seems to be highest in colder waters (37-54 oF). Some fish may be carriers of the virus and exhibit no external signs. The actual presence of the disease can only be determined by laboratory testing.

LCC's Past and Ongoing Projects

Facillitated the discovery of the first confirmed golden clam (Corbicula fluminea) in Lake Champlain. A CHAMP volunteer found it during a survey in Whitehall, NY.

Created CHAMP--a community science volunteer monitoring program to survey and track aquatic invasive species in Lake Champlain.

Worked to secure ongoing funding for control of water chestnut populations.

Developed management plans for the basin's invasive species as a member of the Lake Champlain Basin Aquatic Nuisance Species Task Force.

Sought innovations to limit the amount of pesticide needed to control sea lamprey in Lake Champlain as a member of the US Fish and Wildlife Service Alternative Sea Lamprey Control Task Force.

Helped develop a plan for rapidly responding to new invaders as they arrive and are discovered.

Provide educational materials to help community members stop invasive species.

Successfully advocated for regulations and fines to make the transport of invasive species a crime.

Promoted baitfish regulations to minimize invasive species introductions.

Led efforts to initiate the rapid response plan when Asian clams were discovered in the Champlain Canal.

Undertook vegetation surveys in Missisquoi Bay and the Northeast Arm to assess the prevalence of invasive species and conduct rapid response against any new populations found.